Australian Men's Rights Advocates - AustralianMRA

Family Courts Violence Review 2009 - Australian Government

The Attorney-General commissioned a review of the practices, procedures and laws that apply in the federal family law courts in the context of family violence. The Family Courts Violence Review considered whether improvements could be made to ensure that the federal family law courts provide the best possible support to families who have experienced or are at risk of violence.

Professor Richard Chisholm, former Justice of the Family Court of Australia, was appointed to undertake the review.

In accordance with the Terms of Reference, the review was completed by the end of November 2009, with a report being submitted to the Attorney-General, the Chief Federal Magistrate of the Federal Magistrates Court and the Chief Justice of the Family Court of Australia.

The report is currently being considered by the Attorney-General.

The review focused on the laws, practices and procedures that apply in family law cases that raise family violence concerns. While not directly relating to shared parenting or shared care, all aspects of family law and court practice and procedures were considered to the extent they impact on the federal family law courts’ response to the needs of families affected by family violence.

The 2006 family law reforms, which include the shared parenting reforms introduced in the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006, have been evaluated by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS). AIFS delivered its evaluation report to the Attorney-General’s Department and the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) in December 2009. Further information about this evaluation and a link to the AIFS report can be found on the Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms page.

The Family Law Council’s report on Family Violence can be found on the Family Violence Report page.

The Family Courts Violence Review Report - Australian Government - Professor Richard Chisholm - 2009

website Attorney-General's Department - Australian Government - Family Courts Violence Review

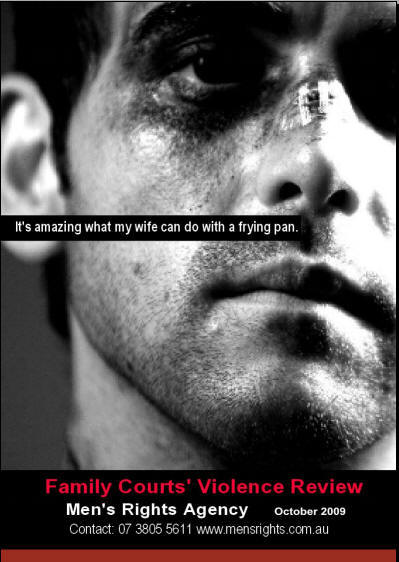

One

of the organizations involved with this issue was The Men's Right's Agency (MRA) whose reply is published below titled

"It's amazing what my wife can do with a frying pan"

In 2006 substantial changes were made to family law legislation with

the introduction of the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006.

The Act provided for a presumption that parents would be declared

suitable to participate jointly in the major decisions in their children's lives, which was

basically a reworking of the

previously described “special issues” consideration, which in turn was a

derivation of the prior "guardianship‟ provisions, but without the attached notion of

parental rights remaining,

just duties and responsibilities.

Following on from this finding of parental suitability, the Act orders

that judges MUST consider shared parenting time etc or if not practical or suitable, then

substantial contact, with the overriding proviso that all decisions made should consider the

best interest of the child.

Equal shared parental responsibility can be rebutted if the court is

satisfied the conflict between the parents is too intense and unlikely to diminish or if there

are „reasonable grounds‟ to believe that a person has engaged in child

abuse or family violence.

At the time when the Bill was introduced this Agency objected to the elevation of the domestic violence issue into the principles and objectives of the Act, particularly as we considered the issue was adequately addressed in other parts of the Act and other State based legislation. One of our barristers was so concerned by the inclusion, he remarked “that this is the Family Law Act, not a manifesto for a women's domestic violence service”.

Undoubtedly, the particular focus on family violence has led to a situation where even publications such as the Australian Master Family Law Guide1 (2008 p282) discusses the issue purely from the perspective of the Act disadvantaging a woman leaving a violent relationship, where she and/or children have been abused as if it never occurs that a man may be the carer of the children and they may be the people at risk of violence and abuse perpetrated by the mother.

1.

CCH Australia Ltd., 2008 Australian Master Family Law Guide,2nd Edition,

CCH Australia

Furthermore, the same text questions the difficulties a women might

experience in leaving a violent relationship if she is then regarded as being

“unwilling to facilitate and encourage a close and continuing relationship between the child and

the other parent”, S60CC(3)(c)

2. The bias displayed by this prestigious guide in failing to recognize

that men and their children can be victims of a mother‟s abuse or even abuse at the hands

of her boyfriend or other family/friends whom she enlists to support her cause is surprising

and should be subjected to widespread condemnation.

No doubt the “elevation of domestic violence” within the Act occurred as

a result of heavy lobbying from women‟s groups, who tend to advise their members to apply

for an easily gained domestic violence order and/or to make false allegations of child

abuse to give them an advantage before the Family Courts.

The portrayal that women are the only victims of interpersonal or family violence is incorrect and the longer this falsehood is allowed to be used as the determining factor guiding the Federal/State governments‟ response to reducing violence within families, the more likely it is their proposals will fail. Providing solutions to “deal with” only one half of the problem has never been a successful strategy and is likely to exacerbate the very problem it seeks to resolve. The abuser, if undetected become more powerful, perhaps resulting in serious harm or death of their victim and the abused, if not recognised, will become more submissive until perhaps they can no longer live with the abuse, take their own life or retaliate with such force the unintended consequence is the death of the abuser. The battered wife syndrome could be said to apply equally well to battered husbands, but our society has convinced itself that women can be excused their violence if they claim to be a victim of abuse – no such allowance is made for men who are abused.

Similarly, if this inquiry should continue under an invalid assumption that only women are victims of men's abuse and children's only risk is from their fathers, then the outcome will

2

Family Law Act 1975 Page | 4

be to put children at greater risk as they are placed with mothers who

may be skilled in hiding the child abuse they commit and/or ignore the signs of abuse

committed by their live-in boyfriend / defacto / step partner preferring to cherish their adult

relationship above the protection of their child.

It is not our intention to deny any violence committed by biological

fathers, but sadly as is known, mothers are more likely to neglect, assault and kill their

children than biological fathers. The children are also at considerable risk from mother's

boyfriends, defactos, step fathers, siblings or other relatives.

This Agency is suggesting a balanced approach should prevail and we

should not be contemplating changes to the Family law legislation based on the sad

death of one little girl or the presumption that only women and children are in need of

protection.

Of course, women and children should be protected from violence and

abuse BUT so should men and children!

Unfortunately, statistical information about the reasons cited for

separation has become fragmented because the latest figures only include data from the Family

Court of Australia3

. A more comprehensive understanding of the reasons cited for the

breakdown of a relationship would have been available if the statistics from the

Federal Magistrates Court had been included. As it is, the percentages of abuse claims are

bound to be higher in the FCoA for this is where most of these cases involving

serious allegations are heard. To gain a true picture of abuse experienced by separating couples

interacting with the Family Courts we need access to the figures from the Federal

Magistrates Court as well. Prior to the introduction of the Federal Magistrates Court, Table

34

, shown below defines abusive behaviours in some detail and shows 9.6% of women and

0.4% of men claim “Physical Violence to you or your children” as the reason for the

breakdown of the marriage.

3 Family Court of Australia, 2009, Shared Parental Responsibility

[accessed online at http://www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/resources/file/eb6b6f033263e7d/SPR_org_02_03_09.doc]

4 Wolcott I. and Hughes, J., 1999, Towards understanding the reasons for

divorce, Australian Institute of Family Studies, [accessed online www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/WP20.pdf] Page | 5

Table 3. Perception of main reason for marriage breakdown by gender

(n=633) Notes: Missing cases=17 (no reason given). 2

(11)=59.38, p<.001 (women’s reports versus men’s reports).

Main Reason Women (n=354) Men (n=279) All (n=633) % n % n % n Affective issues Communication problems 22.6 80 33.3 93 27.3 173 Incompatability / ‘drifted apart’ 19.8 70 22.6 63 21.0 133 You or former spouse had an affair 20.3 72 19.7 55 20.1 127 Abusive behaviours

Physical violence to you or children 9.6 34 0.4 1 5.5 35 Alcohol/drug abuse 11.3 40 2.5 7 7.4 47 Emotional and/or verbal abuse 2.5 9 1.1 3 1.9 12 External pressures

Financial problems 4.0 14 5.7 16 4.7 30 Work/time 1.7 6 3.9 11 2.7 17 Family interference 0.3 1 1.1 3 .6 4 Physical/mental health 4.2 15 5.4 15 4.7 30 Other Spouse’s personality 0.8 3 1.4 4 1.1 7 Children problems 2.0 7 .7 2 1.4 9 Other .8 3 2.2 6 1.4 9 Page | 6

The latest figures from the FCofA5

provides the reasons why both mothers and fathers were only granted a limited amount of contact. However, the figures do

not represent a complete picture for the reasons discussed previously and below. CASES WHERE THE FATHER RECEIVED LESS THAN 30%OF TIME

Note: ‘Other’ includes where the reason is unknown such as; the parties

consenting during the litigation process, the reason is not covered by a category, or

there is multiple and complex reasons.

CASES WHERE THE MOTHER RECEIVES LESS THAN 30% OF TIME

CASES WHERE THE FATHER SPENT NO TIME WITH THE CHILDREN o In 6% of litigated cases, the father was ordered to spend no time with

the children.

o Where the parents came to an early agreement, it was agreed in less

than 1% of cases that the father have no contact with the children.

CASES WHERE THE MOTHER SPENT NO TIME WITH THE CHILDREN o In 1% of litigated cases, the mother was ordered to have no contact

with the children.

5

Family Court of Australia, 2009, Shared Parental Responsibility

[accessed online at http://www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/resources/file/eb6b6f033263e7d/SPR_org_02_03_09.doc]

Mother - when less than 30% time

Abuse and/or FV, 16%

Childs Views, 2%

Distance/ Transport/ Financial Barriers, 16%

Entrenched conflict, 2%

Mental Health, 31%

Relocation, 7%

Substance abuse, 7%

Other, 20%

Father - when less than 30% time

Abuse and/or FV, 29%

Childs Views, 2%

Distance/ Transport/ Financial Barriers, 6% Entrenched conflict, 15% Mental Health, 3%

Relocation, 4%

Substance abuse, 5%

Other, 35%

NOTES:

[1] A sample of 1448 litigated cases were taken from total of 6992 litigated cases finalised in 2007-08 [2] The term „litigated cases‟ includes all Applications for Final Orders finalised, by agreement or judgment, in the Family Court of Australia [3] A sample of 2719 consent cases were taken from a total of 10,575 consent cases finalised in 2007-08 [4] The term „consent cases‟ includes all Applications for Consent Orders finalised in the Family Court of Australia [5] For data collection purposes 50/50 time was defined as between 45 % and 55% of the time spent with a child or children. Page | 7

The main reasons for the order included:

Reason Percentage of cases reviewed overall (1448 out of 6992 litigated cases) Fathers 6% of 6992 cases = 420** Mothers 1% of 6992 cases = 70** Abuse and family violence 38% 160 15% 10 Entrenched conflict 10% 42 0% 0 Distance/transport/financial barriers 0% 0 8% 5 Relocation 2% 8 8% 5 Mental health issues 2% 8 31% 22 Other 42% 176 31% 22 Missing data* 6% 26 7% 4 [1] A sample of 1448 litigated cases were taken from total of 6992

litigated cases finalised in 2007-08

There is also no explanation about how the cases to be reviewed were

selected. Were the participants selected randomly or was another criteria applied?

As already noted, cases from the Federal Magistrates Court were not included,

neither were interim decisions. Anecdotal evidence over 15 years tells us that a

considerable number of cases go no further than an interim hearing. The writer does

recall at the time of the study, the then Chief Justice of the Family Court, Alastair

Nicholson did refuse to allow the Canberra staff to supply, even the number of fathers

and mothers participating and how they were recruited.

Notwithstanding, the questions regarding the selection of the reviewed

cases it is interesting to note the significant difference in reasons given for “no

contact” orders being applied to mothers and fathers. The main criteria for fathers are

Abuse and family violence and mothers – Mental health issues. However, if we

recognize that symptomatic of mental health issues, depending on the diagnosis, can be

a tendency towards violent behavior. This is particularly the case with

bipolar

6

mood disorders. It is possible that some mothers have been categorized as

having mental health issues rather than being classified as abusive and violent in an

attempt to minimize and excuse women‟s violence. Again we are frequently told of a

father‟s knowledge or suspicion that his wife is suffering from a mental disorder

– most often described as “bipolar”.

6

Carlson N.R. and Buskist W., 1997, Psychology: The Science of Behaviour,

Allyn and Bacon, USA, (p 593) * Not all categories are shown in this table therefore it does not add

to 100%. „Other‟ includes where the reason is unknown such as; the parties consenting during the litigation process, the reason is not

covered by a category, or there is multiple and complex reasons. **The FCofA has not explained whether the percentages shown in the

tables apply to the 1448 reviewed cases only or applied to 6992, the

overall number of litigated cases. Page | 8

If we combine the two categories of Abuse and family violence and mental

health issues, 40% of these particular fathers were denied contact for these

reasons and 46% of mothers. However, these percentages cannot be taken as

representative of Australian separating population.

Clearly problems of parenting in fathers are more likely to be described

as Abuse and family violence and in mothers as mental health issues, although the

statistical difference would seem to be contrary to the data available for child

abuse and now family violence gathered from State Government departments.

Mental health pleadings are tendered for consideration when a mother is

accused of killing her children, but rarely when a father is accused of a similar

crime. Despite the difficulty of imagining that any person who kills their own child

could be described as “being in their right mind,” fathers are, more often than

not, held fully accountable for their actions and mothers are excused due to their

claimed incapacity.

In the following pages we present data detailing the numbers of

victims/perpetrators of domestic violence and child abuse. Where possible we have included

the gender of the person who is the victim or perpetrator and their relationship to

each other. 9 | Page

Misuse of domestic/family violence legislation and making false

allegations:

In 1991, Supreme Court Justice Terence Higgins7

, when overturning a Canberra woman‟s domestic violence protection order against her estranged

husband, described “as nonsense the woman‟s assertions that the statements attributed to

the man had represented a threat to her safety” and he further said “the woman was a

liar and that she and her sister have fabricated their allegations”. Justice Higgins

pointed out that “harassing or offensive behavior could justify an order if the spouse

feared for her safety. But that fear had to be an objective one and a reasonable

response to the situation. “Mere criticism, nagging, even unreasonable persistence

cannot credibly be described as „violence”.

His Honour questioned the practice of the Magistrates Court “in issuing

protection orders merely to prevent annoyance by one party to a domestic

relationship of another” and suggested that in this case “it seems to me that the

resources directed towards eradicating or at least controlling violence in our society are

being sadly misdirected”. He concluded the woman‟s evidence was deliberately false

and revealed a consistently vindictive attitude.

In 1995, Queensland’s Chief Stipendiary Magistrate Mr Stan Deer

acknowledged the problem of domestic violence orders being misused when he stated

“some women are using domestic violence orders to gain a better position in child

custody cases”

8

.

Estimates provided to this Agency at the time, by court

staff/prosecutors suggested that only 5% of applications for domestic violence orders were

legitimate in their claims.

In 1999, a survey conducted with 60 serving NSW magistrates, conducted

by the Judicial Commission of NSW found that most (90 percent) believed

domestic violence orders(AVOs) were used by applicants – often on the advice of a

solicitor – as a tactic in Family Court proceedings to deprive their partners of access to their

children9

.

7

Canberra Times XYZ 8

Horan, M., 1995, Women abusing violence orders: top SM, Courier Mail, 5

July 1995, Brisbane 9

Noonan G., 1999, Call for tougher checks on AVOs, Sydney Morning Herald,

30 August 1999, Australia and 10 | Page

A further study of Queensland Magistrates found three out of four who

responded believed parents use domestic violence protection orders as a tactic in

divorce and custody battles10

. Like their counterparts in NSW several Queensland Magistrates believed many women applied for domestic violence orders on the advice

of their solicitors.

An extract from an email communication from a female friend (an academic

and health professional) to a woman, separated from her husband, advising

her on how to effect a separation provides an example of the attitude towards using

the domestic violence legislation for nefarious purposes: From: Mary@XYZ.edu.au To: Joanne@12345.com

No need to thank me for the coffee this morning darling. Its [sic]

always a pleasure to catch up with you. If you want David out of your life altogether that AVO idea

isn‟t as silly as it sounds, is it? A few crocodile tears in front of a stupid cop and they will be happy to

do all the work for you. You will be back sunning yourself in (coastal town) before David‟s feet hit

the ground. Put yourself first Joanne. You are single now, you don‟t have to worry about his feelings

any more.

Joanne wrote previously: Thanks for the coffee this morning. Can‟t believe I left home without my

purse! Got a lot on my mind I suppose. David was here today, he is moving to a unit in

(suburb)! Says it will be great because it is across the road from the school. Says he want the kids to

stay over 2 nights a week! Woe is me. Joanne Having had one AVO interim order dismissed, the mother tried to take out

another and again sought the advice of her friend, Joanne:

July 2006 Hi Mary, Big day for me today – not nice either. I wonder if you can help me with

something…

Online Executive Summary, Judicial Commission of NSW http://www.judcom.nsw.gov.au/Monograph20/Executive%20summary.htm (no

longer available at this URL)

10

Nolan J., 2001, Domestic violence orders „abused‟, Courier Mail 14 March

2001, Brisbane, Queensland, and Field R., and Carpenter B., 2003, Issues relating to Queensland

Magistrates Understandings of Domestic Violence, School of Justice Studies, QUT Brisbane [accessed online at

http://eprints.qut.edu.au/3726/1/3726.pdf] 11 | Page

The constable who came on Saturday would not take out an AVO for me so I

have to start again with another officer but I was told that I should write a letter of

complaint about him first. Trouble is I don‟t know what to say. If I were to get some ideas together would you

be willing to draft the letter for me? Please don‟t agree unless you feel comfortable with

this.. Joanne. Mary replied: Of course I can! I‟ll try and give you a call later to see what the lawyer said. M. The mother moved away taking the children with her and the father found

himself in receipt of another AVO issued by another police officer in another

place. He was also arrested for an alleged breach and eventually cleared. This

father spent $140,000 to clear his name and reestablish contact with his children

again – all because of the ease of taking out a „fake AVO‟.

Another father has survived 5 AVO applications based on false

allegations the wife made to the police. This has resulted in 10 court appearances –

all dismissed. The father complained to the Judge on the last appearance and

she said, “she didn‟t care if it was the 90th

application that there are new allegations and they must be tested in court”.

Other fathers have expressed their experience in this way:

John says: I called the police once because my partner was hitting and throwing

things at me. The officers talked to both of us individually and seemed understanding. The joke

came when the officers came back up and said yes you were right in calling us and she is out of

control but you need to leave the premises because if they get a call again to this premise I

will be the one going to the lockup for the night. I asked why and the answer was that the man is

the one who gets taken away for the night. How is this fair? She was the aggressive one.

I will lay money down if the roles were reversed I would have been taken away and charged. Now if

someone can tell me how that is justice I would like to hear it.

Or Michael described to MRA his experience as follows: He called the police to calm his mentally ill wife and prevent her from

taking off in the middle of the night, worried she might harm herself. Following procedure, the

couple was separated, the 12 | Page

female officer talking to his disturbed wife and the male officer

talking to Michael. The outcome: Michael was arrested and bailed several hours later and told

not to return to his house. Michael was his wife‟s day to day support, his wife knew she

relied on him and was devastated when she realised the outcome of the police actions. The

police aggressiveness, unwillingness to listen to the real problem and determination to proceed

using the domestic violence legislation nearly tore this couple apart. Neither party wanted

to proceed with a DVO. The interim application was refused, but a mix up with the dates for the

next hearing meant the respondent husband was not present. An adjournment requested by his

solicitor was refused and a final order made without hearing his side of the story. During the

application made by the husband to revoke the order, which was supported by his wife, the

Magistrate identified that the husband had been “seriously prejudiced” by the making of the order

under those circumstances. Many thousands of dollars later spent in legal fees, the

Magistrate revoked the DVO.

Or in David’s words:

This year I experienced first- hand the bias shown toward men when they

try to seek protection. On 6 occasions I tried for a DV orders after being verbally

abused and physically attacked, including times in front of my 4 year old daughter. The Police

were called on 2 occasions, and each case I was advised to seek a DV order. My lawyer

handling the legal matters advised me to seek a protection order. But it seems that the

staff at the courts had different ideas, in fact the indifference shown by the staff was

insulting. When I set out to protect myself and my children from the violence and

abuse by an ex partner and her boyfriend the application should not be so easily

dismissed. To be told "that is a matter for the family courts" is just wrong! To add insult to injury,

when the ex found out that I had been recording conversations, she was IMMEDIATELY granted an

intervention order. The other allegations were "not paying bills and using her credit card".

There has NEVER been any physical violence on my part, nor listed on her intervention order.

She found out after I made it known that my lawyer and I had a copy of the conversation where

she and her new boyfriend made threats of "putting a bullet in my head" and "taking me

to the police station and beating the shit out of me". And this is justice???

To ignore the violence committed against men and their children, who

have been victimized and abused by the very person expected to nurture and care

for them is both discriminatory and colluding to excuse women‟s abusive/criminal

behavior. 13 | Page

British philanthropist Lord Astor remarked in 1993: “Everyone starts out totally dependent on a woman. The idea that she

could turn out to be your enemy is terribly frightening”

11

Perhaps this explains in part, why there is such a reluctance to

acknowledge women‟s capacity for violence. Or as we have previously observed, the promotion

of “women only as victims and men only as perpetrators” has enabled many pro- feminist

organizations to fund their continuing existence with public monies handed out by

politicians who see more votes in providing services for women and children than for men and

children. Greed is a powerful motivation to ignore others who need assistance as

victims of women‟s violence.

Many millions of dollars have been provided at both federal and state

level for counselling and refuge services for women. Ask the question – is

violence against women reducing at a rate commensurate with the expenditure? It is

reducing, but perhaps improved responses would produce a more noticeable reduction and

monies intended to protect victims of violence could be directed towards those

people, rather than to people who claim to be victims for ulterior purposes. Then

consider asking the question: why is women‟s violence against men increasing? Statistics

confirm this and some commentary has appeared in the media in relation to younger women‟s

aggression and violence as well.

Services for men are limited to a small number of anger management

courses. The greatest indignity for any man who is a victim of abuse is to be

referred to an anger management course, as if the abuse they have suffered is their fault.

MRA has been aware of this occurring numerous times. It sounds absolutely contrary to

the mantra of women‟s groups – “the violence is never her fault” doesn‟t it?

Perhaps, somewhat cynically, we should add a rider to clarify that this

statement only applies to women who are victims. If you‟re a male victim, then your

female attacker seemingly has every right to claim it‟s not my fault, he made me hit

him!

11

Pearson, P., 1997, When she was bad: Violent Women the Myth of

Innocence, Viking Penguin, USA 14 | Page

Anger management courses for women are few and far between!

Police frequently ask men seeking protection from a female abuser, “what

did you do to make her hit you?” Then suggest they should be “be a man about it”

asking “are you a whimp or what?”

For a man who is a victim of abuse and who is trying to protect himself

and his children it is difficult enough to admit being abused by his wife without being

exposed to this unhelpful reaction when seeking the assistance from the authorities.

This administrative abuse is not restricted to police only. Over the

years our clients have frequently reported difficulties in making a court appearance – refusal

to accept applications; refusal to arrange urgent hearings for temporary

protection orders; of being asked to wait in a room away from the court, while the hearing into his

application for protection is heard in his absence and as you might have anticipated – a

protection order is refused because he didn‟t appear; being given a wrong time for

appearance or the magistrate refusing point blank to hear his evidence or finally a

failure by the police to serve the initiating summons or the domestic violence orders on women

who are perpetrators of abuse.

Other men who have committed no violence/abuse whatsoever, are persuaded

to accept a domestic violence order „without admissions‟ after being

persuaded that the outcome is not going to affect his life or his contact with his

children. Various reasons are put forward such as “why spend the money on defending the wife‟s

application – you don‟t really want to see her anyway!” Or “The order is only a civil

order” without explaining that the DV order is entered onto the police data base and

they could be accused at anytime of breaching the order, which then becomes a criminal

offence and the existence of any DV order is going to be used against them in future

hearings, especially those involving family issues. 15 | Page

Correcting the false, mistaken or misleading presentation of statistics

in relation to interpersonal and family violence:

The following is a small sample of the statistical evidence available

from Australian data which illustrates a significant number of men/husbands/partners are

the victims of interpersonal/family violence.

1999 – In South Australia 32.3 per cent of victims of reported domestic

violence by a current or ex-partner (including both physical and emotional violence

and abuse are male

2005 – In New South Wales 28.9 percent of domestic violence assault

victims are men12

2005-2006 – In Victoria 26.45% of adult domestic violence victims are men according to police records13.

2006 – In Australia 29.8 per cent of victims of current partner violence since the age of 15 are male14

2009 – In Queensland 39.9 of domestic violence orders were issued to protect men15

12

Peoples, J. (2005). “Trends and patterns in domestic violence assaults”,

in Contemporary Issues in Crime & Justice, No 89, October, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/vwFiles/cjb89.pdf/$file/

cjb89.pdf); 13

Victims Support Agency, 2008, The Victorian Family Violence Database

Volume 3): Seven-Year Report, Victorian Government, Department of Justice 14

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2005). Personal Safety Australia

(http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/ 4906.02005%20(Reissue)?OpenDocument) 15

Queensland Department of Communities, Gender based domestic violence

orders and applications made between 2004-05 and 2008-09 16 | Page

Domestic and family violence orders: Number and type of order by gender,

Queensland, 2004-05 to 2008-09 Department of Communities, October 2009

Temporary protection orders Protection orders Males Females Unknown Total Males Females Unknown Total 2004-05 2,535 5,181 559 8,275 5,650 6,057 2,187 13,894 2005-06 1,945 5,576 84 7,605 4,331 8,889 347 13,567 2006-07 1,937 5,592 51 7,580 4,501 8,585 219 13,305 2007-08 1,871 5,255 52 7,178 4,423 8,201 234 12,858 2008-09 2,285 5,732 165 8,182 5,395 7,616 481 13,492

Temporary Protection Orders issued by gender 2004-05 to 2008-09

Protection Orders issued by gender 2004-05 to 2008-09 0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09

Male

Female

Unknown

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

10,000

2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09

Males Females Unknown 17 | Page

Domestic and family violence applications: Number and type of application by gender, Queensland 2004-05 to 2008-09 Department of Communities, October 2009

The above statistics from the Queensland Department of Communities

confirms the growing incidence of men as domestic violence victims. Page | 18

Many International studies support the claim that women and men can be

equally violent to each other, with women becoming increasingly violent For further

information on these studies we refer you to Professor Martin Fiebert‟s updated

bibliography16

which examines 256 scholarly investigations: 201 empirical studies and 55 reviews

and/or analyses, which demonstrate that women are as physically aggressive, or more aggressive,

than men in their relationships with their spouses or male partners. The aggregate

sample size in the reviewed studies exceeds 253,500.

The great taboo …… silencing the truth about domestic violence Researchers and women‟s advocates have found little opposition to the

reams of research they have produced over the past thirty years, much of which could be

described as self-

select opinion polling.

UK neurophysiologist Dr Malcolm George, who has spent many years

commenting on domestic violence, and researching „men as victims‟ refers to Kate

Fillion‟s comments to support his explanation of the methods use to “silence the truth” about

domestic violence.

17

When initial evidence of the gender equality of intimate violence

emerged in the work of Straus et al. (1980), the authors faced not only criticism but also a barrage of abuse,

falsehoods and threats from women's advocates that is now well documented (Gelles, 1994; Luccal, 1995;

McNeeley, Cook, & Torres, 2001; Straus, 1993). Similarly, when attempting to resurrect the argument,

McNeeley (see McNeeley & Robinson-

Simpson, 1987) also faced hostility and abuse. Robinson-Simpson was

allegedly an oppressed female who had been duped by a malevolent misguided male (McNeeley, Cook and

Torres, 2001). As a result, according to Fillion (1997): Currently, findings on all types of female physical and sexual

aggression are being suppressed; academics who do publish their research are subjected to bitter attacks

and outright vilification from some colleagues and activists, and others note the hostile climate and

carefully omit all data on female perpetrators from their published reports. (pp. 229-230) This suggests that some twenty years of silencing had occurred beginning

with publications in the mid- to late-1970s. (Dr. Malcolm George)

16 Fiebert, M.S., July 2009, References examining assaults by women on

their spouses or male partners: an annotated bibliography, California

State University, Long Beach, USA [Accessed online http://www.csulb.edu/~mfiebert/assault.htm

] 17 Malcolm J. George "The "great taboo" and the role of patriarchy in

husband and wife abuse". International Journal of Men's Health.

FindArticles.com. 29 Jun, 2009. [ accessed online http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0PAU/is_1_6/ai_n27283522/]

Page | 19

Australian Micheal Woods, a Senior Lecturer with the University of

Western Sydney confirms18

: The domestic violence industry in Australia is a multi-million dollar

enterprise, ostensibly designed to ensure that women live free of violence. However, it seems that some sections

of this industry such as the White Ribbon Campaign (WRC) are engaging in the use of dishonesty to further

the interests of organisational growth rather than contribute to addressing a social problem. While

questions of probity are important where substantial amounts of government funds are involved, the dishonesty

being practiced is also contrary to the interests of those women the industry claims to champion.

John Coochey, a well informed critic of the misuse of poorly conducted

research told the Australian Crime Commission conference19

:

It is in the Australian Capital Territory that this lack of intellectual

rigor seems to have reached its zenith. In March 1996 the ACT Department of Health released a report entitled

Review of ACT Sexual Assault Services (9) which stated without any evidence that one in four women had been

the victim of sexual assault. It was largely based on an earlier report Many Paths for Healing prepared by

the Canberra Women's Health Centre, funded by the Commonwealth and Territory Governments. This had found 20

per cent of respondents to a survey had been the victims of organized ritual abuse, formerly known as

satanic ritual abuse-black masses torture chambers etc. This obviously means the ACT must have more covens

complete with torture chambers than Catholic Grammar schools. And absolutely ridiculous study,

but which was accepted publicly by the ACT Government! In fact a British Government study found only

three such cases over a four year period and in the US only one out of 12,264 cases was substantiated. The

origin of this insanity can perhaps be found in the WHS report, page 7.

"Feminist research methodology

· The distinction between subjective and objective research is rejected.

All research occurs in a social context and reflects the researchers‟ way of seeing the world.

· The production of emancipatory knowledge and empowerment of those who

are being researched is a central focus.

· The research process should contribute positively to consciousness

raising and transformative social action"

Published content within Beyond these walls, a report from the

Queensland Domestic Violence Taskforce 198820

provides an early example of blatant misuse of others‟ research.

18 Woods. M., 2006, Dishonesty in the domestic violence industry,

University of Western Sydney, Australia 19

Coochey, J., Myths and Realities or All the Facts that Fit we Print,

Australian Crime Prevention Council, Melbourne 17 - 20 October

1999.citing Courtney, J Williams, L, 1995, Many Paths to Healing: the counseling….

Canberra Women’s Health Centre

20 Queensland Domestic Violence Taskforce, 1988, Beyond these walls Page

| 20

On page 47, a table taken from the Conflict Tactics Scale method of

research (Straus and Gelles 1986) is illustrated. It shows the category "Husband to Wife

Overall and Severe Violence, but neglects to show the 'other half' of the table – the

column showing “Wife to Husband” violence. If the other column had been included it would have

shown women were equally violent and in some categories more so, challenging the

authors‟ statements made on page 16 that they would refer to the perpetrator by the

"masculine pronoun and the victim - the feminine".

The authors chose to engage in academic misrepresentation and were

dismissive of the 41 male respondents out of a total of 661 who answered the

questionnaire. This dishonest report formed the basis for the creation of the Queensland response to

domestic violence.

Research can be easily manipulated – by asking the questions one knows

will produce the response one is seeking or by ensuring those who might give unwanted

answers are never given the opportunity to respond.

The Queensland Crime and Misconduct Commission was tasked to report on

the Queensland Police response to domestic violence21

. The writers claim to have consulted widely with domestic violence victims, the judiciary, police and

domestic violence and women‟s legal service providers. They note that “Most survey

participants were female (one male participant)” and that “only one person indicated that the

perpetrator of domestic violence was female”. (p.8) Quite how the CMC expected to reach male victims of domestic violence we

are unsure, particularly when questionnaires were only issued via women‟s domestic

violence services and those services do not have contact with male victims – their door is

firmly closed to them. Needless to say, the CMC did not contact this Agency.

Michael Flood, one of the authors of a report

22

written for the 2008 White Ribbon Day campaign has been forced to acknowledge they incorrectly published a

statement relating to teen violence, which resulted in considerable damage to the

reputation of young Australian men.

21

Queensland Government, 2005 Policing domestic violence in Queensland:

Meeting the Challenges , Crime and Misconduct Commission, Queensland.

22 Flood M. and Fergus, L., 2008, An Assault on Our Future:The impact of

violence on young people and their relationships, White Ribbon Day [the corrected version is online

using the excuse of a typographical error http:// www.whiteribbonday.org.au/media/documents/23546WhiteRibbonYouthSummary.pdf]A

White Ribbon Foundation Report Page | 21

Flood and Fergus wrote: “that one in three boys believed it was not a

big deal to hit a girl”, making headlines around the world!

The statement which was taken from an original report by the National

Crime Prevention 2001 study23

into teen violence referred instead to "girls hitting boys".

Men‟s Health Australia researcher Greg Andresen, who uncovered the

blatant misrepresentation, persisted in securing a retraction from the ABC and

other media.

A media release from Men‟s Health Australia24

details that the NSW Government has confirmed making substantial errors in its current Discussion paper on

NSW Domestic and Family Violence Strategy. In errata published on the Office for Women‟s

Policy webpage, the Government admits errors that clearly over-inflate the female

victimisation rate from partner assault by at least 65 per cent while downplaying the prevalence

of violence against men by their former partners.

Academic researchers have been guilty of hiding the facts or have been

so swayed by the prevalent agenda and media messages portraying men/husbands/fathers as

being the violent ones, their ability to design studies that will expose the true

status of abuse and violence has been affected. Studies are only as good as the questions

asked and if the right questions are not asked then policy makers will continue to be fooled by

the agenda to protect women as entirely innocent victims, never the perpetrator or as

the person who encourages another to perpetrate abuse on her behalf.

We also refer you to the following attachment:

Do we ignore men who are victims of domestic violence25

details the available evidence, showing the level of IPV/family violence committed against men is far

too high to be ignored any longer? The current government has chosen to focus on

providing assistance only for women and children who may be victims of violence, ignoring men

who find

23 National Crime Prevention (2001) Young People & Domestic Violence:

National research on young people’s attitudes and experiences of

domestic violence. Canberra: Crime Prevention Branch, Commonwealth Attorney-

General’s Department. 24

Andresen, G., 2009, Call to stop demonizing men and boys, [ accessed

online http://www.menshealthaustralia.net/files/MHA_Release_030909.pdf]

25 Woods, M., and Andresen, G, 2009, Do we ignore men who are victims of

domestic violence, Men’s Health Information & Resource Centre University

of Western Sydney and Men’s Health Australia [accessed online at http://www.menshealthaustralia.net/files/WRD07.pdf]

Page | 22

themselves in a similar situation. These policies suggest the Government

has rejected their obligation under the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights which clearly dictates that discrimination based on „sex‟ is prohibited.

Statistics detailing who’s responsible for child neglect, abuse and

homicide Child Abuse In 2007, Desley Boyle the then Minister for Child Safety in Queensland

issued a press release26

: “People may be surprised to hear that women, just as much as men are

responsible for child abuse,” Ms Boyle said.

“We have an idealised image of mothers – that they feed their kids

before themselves – but I‟m sorry to say, it‟s not always true.”

Dads not the demons27

, a fact sheet containing data accessed via FIO from the Department of Child Protection (DCP) in Western Australia highlights

statistical evidence to show that natural mothers are far more likely to abuse children than their natural fathers. The DCP should be congratulated in properly defining the relationship of the abuser to the child. For too long now departments involved in child protection throughout Australia have failed to properly categorise “men” into de factos, live-in boyfriends, step fathers, other male visitors, and biological fathers

etc., creating a false impression that fathers present a far greater risk to their children

than is evident. In other studies instead of categorising biological fathers and mothers they

might be described as „parents‟ only, again creating a false impression.

26 Boyle, D., 2007 Dads and Mums responsible for child abuse and

neglect, Ministerial Media Statements, 11/04/07, Queensland Government

27 Woods, M., and Andresen, G, 2009, Dads not the demons, Men’s Health

Information & Resource Centre University of Western Sydney and Men’s

Health Australia [accessed online at http://www.menshealthaustralia.net/files/dads_not_the_demons_09.pdf]

Page | 23

The above chart focuses on abuse committed either by a mother or father,

but it is interesting to view the full table of statistics for 2005-2006 from the

West Australian Department of Children detailing the relationship of the abuser to the

victim.

The recognition has been a long time coming and still most government

authorities charged with „keeping the books‟ fail to define the exact relationship

of the abuser to the child.

The West Australian Department of Children is the first to provide via

FOI application a detailed breakdown of the relationship of the person believed

responsible for the abuse to the child.

Surely this level of evidence of just who commits abuse against children

cannot be ignored any longer?

Child Homicide: In recent times it has been uncovered that the Australian Institute of

Criminology had published incorrect statistics relating to the homicide of children and

the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim.

28

The following commentary and chart provides the correct statistics and clearly identifies mothers as killing more children than

biological fathers.

28 Andresen G., Men’s Heath Australia http://www.menshealthaustralia.net/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=750&Itemid=102

Page | 24

Mother‟s boyfriends are also identified as killing children who are not

their biological off spring.

The Australian Institute of Criminology has recently corrected an error

in its National Homicide Monitoring Program 2006-07 Annual Report

29

. The original report stated that 7 homicides involved a mother and 15

involved male family members. The corrected report states that 11 homicides involved a mother

and 11 homicides involved a male family member. When the category of 'male family member'

is broken down, we see that only 5 perpetrators were fathers, while another 5 five were

de-facto partners of the mother who lived with the child (one father murdered two children).

Importantly, no child victims were killed by a complete stranger in 2006–07.

The AIC has also acknowledged that "the usage of male family member and

mother is not a useful way of classifying relationship between a child homicide victim and

their offender. In future reports we will employ classifications that provide a more detailed

classification of the relationship between child victims and offenders."

According to a NSW report

30

into the deaths of the 60 children, who died in violent circumstances between January 1996 and July 1999, mothers were

responsible in the majority of cases.

The Fatal Assault of Children and Young People report published in 2002

disclosed that more children died as a result of the mother‟ violence/neglect than as a

result of the biological father‟s violence/neglect.

29 Australian Institute of Criminology, 2006-07 National Homicide

Monitoring Program 2006-07 Annual Report, http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/current%20series/mr/1-20/01.aspx

30 Fattore T. and Lawrence R., The Fatal Assault of Children 2002,

Commission for Children and Young People, NSW Page | 25

The report divides the deaths into four categories, non-accidental

injury, mental illness, family breakdown and teenage.

In the first category - non accidental injury, there were 19 deaths. In

9 cases, the primary suspects were men and for the remaining 10 it was the children‟s mother.

Of the nine male offenders, 5 were designated as the mother‟s boyfriend, 1 a border known

to the child and only 3 being the biological father.

In the mental illness category all 11 deaths resulted from the mother‟s

violence.

In family breakdown, of the 7 incidents, 3 were committed by the father

and 4 by the mother. More than one child was killed in three cases.

The teenage category resulted in 13 deaths, none of which were committed

by parents or defactos. 12 were committed by males and 1 by a female.

The results across all four categories show: 26 females and 25 males

killed children under 17 years old. Excluding the findings in the teenage category, we find

that of the 12 remaining males identified as primary suspects, 6 were biological

fathers, 5 defacto boyfriends and 1 live-in border.

Overwhelmingly this report shows mothers are over 4 times more likely to

kill their children than biological fathers.

In 2000, researcher Jenny Mouzos included in her 10 year homicide study,

Homicidal Encounters the statement that “Biological parents, usually the mother,

were responsible for a majority of child killings in Australia. Very rarely are children

killed by a stranger”.

Despite this information being put to Government Ministers and more

recently to the Attorney General. Rob McClelland there is still an unacceptable level of

denial that mothers present a far greater risk to the safety of their children than

biological fathers. To highlight the case of Darcey Freeman, who was allegedly killed by her

father after the parents rewrote their parenting agreement or a new parenting order was

issued by the Family Court of Australia, reducing the time the children could spend

with their father as being an event precipitating this inquiry is incomprehensible.

Particularly, when less than Page | 26

12 months prior a woman, Gabriella Garcia strapped her 22 month old son

to her chest and jumped from the same Westgate Bridge, fearing she was about to lose

custody of her son. The father denied he was making any applications for residency to

the family courts. The media did not give the same coverage to this murder/suicide at the

time and the father‟s family have complained recently amidst the furore surrounding

the Darcey Freeman death. Anita Allen, Oliver‟s aunt wrote: “When my little nephew died at the hands of his mother, it went almost

unnoticed because she committed suicide, there was little the media could say. And because

it was a closed coronial investigation, there is little my family know about this

tragedy other than our own loss, disbelief and grief. How could she? It seems that my nephew‟s life

became invisible because his mother killed herself in the process.”

Apart from calls to fence the sides of the bridge to prevent „jumpers‟

little was mentioned in the media. When the media does cover a woman killing her children

they seem to go to extreme lengths to provide excuses for her actions – “she loved her

children to death” or as was recently reported, Garcia took a “Deadly bridge leap to „save son

from a bad life‟

31

. Comments were sought from an expert to relay the impression her actions

were irrational. We would have to agree! According to the journalist:

Detectives found the shared custody arrangements were “amicable”. According to the coroner‟s summary of the incident compiled by the

homicide squad, it was at this time that Garcia became convinced that Allen (the father) wanted to

claim full custody and was poisoning Oliver‟s mind against her.

She further believed that Allen was teaching Oliver objectionable and

abhorrent things about her. There is no direct evidence to substantiate these thoughts or

verify that Allen was making any attempt to secure the full custody of his son”, it read.

Fathers are not offered any such excuse, although it would seem to be

quite reasonable to suggest that „no one in their right mind‟, mother or father, kills their

children.

There are many examples of mothers killing their children, some in

response to family law orders and these have been detailed in an extensive submission from

Nuance. We do not intend to repeat the listing, but refer the Inquiry to the submission.

31

Rout M., 2009, Deadly bridge leap to „save son from bad life‟, The

Australian, p 1. 14 July 2009, News Ltd. Page | 27

The evidence of mothers killing their children has been known for many

years, but the extent has remained largely hidden from public view because the killings

are viewed as an aberration of the mind rather than a deliberate act. We have noted over

the years that mothers arrested for such crimes are more likely to be referred to a

psychiatric institution, medicated, remaining there until she responds satisfactorily to the

treatment, when she will, more than likely, be released.

Family Violence and the Family Law Act It needs to be said at this stage that only a minority of parents cause

harm to their children or each other. When serious abuse occurs it should be handled via the

normal channels at a State level, under their respective criminal codes. The domestic

violence legislation has confused the boundaries for dealing with criminal assault. A civil

response not only allows the authorities to ignore cases requiring some investigation and

possible prosecution, it has allowed the State to provide an avenue for disgruntled partners to

avenge themselves for the smallest of perceived insults. Just by calling the police and making

the wildest of accusations, without any proof whatsoever, and unwanted partner/parent

can be removed from their home and denied contact with their children.

We are concerned the purpose of this inquiry is to draft legislation

that will instruct the FCoA judiciary to „take more notice of domestic violence orders‟ despite the

existence and clear guidance contained in the: Family Law Act 1975 – S.68R Power of court making a family violence

order, to revive vary, discharge or suspend an existing order, injunction or arrangement under

this Act.

We consider the above and other sections contained in the Act adequately

cover the need to take the question of abuse into account.

Suggestions have been made this Inquiry may lead towards encouraging the

States to adopt the family violence legislation now used in Victoria.

The legislation has been expanded to include not only violence and

threats of violence, damage to or threat of damage to property, but to cover various other

issues described as „social values‟.

The Preamble to the Victorian Family Violence Protection Act 2008

states: Page | 28

Preamble In enacting this Act, the Parliament recognises the following

principles— (a)that non-violence is a fundamental social value that must be

promoted; (b)that family violence is a fundamental violation of human rights and

is unacceptable in any form; (c)that family violence is not acceptable in any community or culture;

(d)that, in responding to family violence and promoting the safety of

persons who have experienced family violence, the justice system should treat the views of victims of

family violence with respect. In enacting this Act, the Parliament also recognises the following

features of family violence— (a)that while anyone can be a victim or perpetrator of family violence,

family violence is predominantly committed by men against women, children and other

vulnerable persons; (b)that children who are exposed to the effects of family violence are

particularly vulnerable and exposure to family violence may have a serious impact on children's

current and future physical, psychological and emotional wellbeing;

(c)that family violence— (i)affects the entire community; and (ii)occurs in all areas of society, regardless of location,

socioeconomic and health status, age, culture, gender, sexual identity, ability, ethnicity or religion; (d)that family violence extends beyond physical and sexual violence and

may involve emotional or psychological abuse and economic abuse; (e)that family violence may involve overt or subtle exploitation of

power imbalances and may consist of isolated incidents or patterns of abuse over a period of

time. The Parliament of Victoria therefore enacts:

PART 1—PRELIMINARY 1 Purpose The purpose of this Act is to— (a)maximise safety for children and adults who have experienced family

violence; and (b)prevent and reduce family violence to the greatest extent possible;

and (c)promote the accountability of perpetrators of family violence for

their actions.

We query when the legislators decided it was tolerable to include

statements about the gender of the people expected to offend against any act? Profiling on a

gender basis has never been considered acceptable and could be construed as generating

hatred against men. Some of the issues described in the Act can hardly be claimed to

constitute „violence‟. The legislators in Victoria obviously consider they are entitled to

impose a kind of Kafkaesque doctrine of behaviour on the general public. When legislation

is drafted to impose a standard of behaviour that is reliant on another‟s

interpretation of acceptability the Government is intruding too much. Page | 29

5 Meaning of family violence (1)For the purposes of this Act, family violence is— (a)behaviour by a person towards a family member of that person if that

behaviour— (i)is physically or sexually abusive; or (ii)is emotionally or psychologically abusive; or (iii)is economically abusive; or (iv)is threatening; or (v) is coercive; or (vi)in any other way controls or dominates the family member and causes

that family member to feel fear for the safety or wellbeing of that family member or another

person; or (b)behaviour by a person that causes a child to hear or witness, or

otherwise be exposed to the effects of, behaviour referred to in paragraph (a). Examples The following behaviour may constitute a child hearing, witnessing or

otherwise being exposed to the effects of behaviour referred to in paragraph (a)— overhearing threats of physical abuse by one family member towards

another family member; seeing or hearing an assault of a family member by another family

member; comforting or providing assistance to a family member who has been

physically abused by another family member; cleaning up a site after a family member has intentionally damaged

another family member's property; being present when police officers attend an incident involving physical

abuse of a family member by another family member. (2)Without limiting subsection (1), family violence includes the

following behaviour— (a)assaulting or causing personal injury to a family member or

threatening to do so; (b)sexually assaulting a family member or engaging in another form of

sexually coercive behaviour or threatening to engage in such behaviour; (c)intentionally damaging a family member's property, or threatening to

do so; (d)unlawfully depriving a family member of the family member's liberty,

or threatening to do so; (e)causing or threatening to cause the death of, or injury to, an

animal, whether or not the animal belongs to the family member to whom the behaviour is directed so as to

control, dominate or coerce the family member. (3)To remove doubt, it is declared that behaviour may constitute family

violence even if the behaviour would not constitute a criminal offence. 6 Meaning of economic abuse (a)in a way that denies the second person the economic or financial

autonomy the second person would have had but for that behaviour; or (b)by withholding or threatening to withhold the financial support preventing a person from seeking or keeping employment; coercing a person to claim social security payments; coercing a person to sign a power of attorney that would enable the

person's finances to be managed by another person; coercing a person to sign a contract for the purchase of goods or

services; coercing a person to sign a contract for the provision of finance, a

loan or credit; Page | 30

coercing a person to sign a contract of guarantee; coercing a person to sign any legal document for the establishment or

operation of a business.

7 Meaning of emotional or psychological abuse For the purposes of this Act, emotional or psychological abuse means

behaviour by a person towards another person that torments, intimidates, harasses or is

offensive to the other person. Examples— repeated derogatory taunts, including racial taunts; threatening to disclose a person's sexual orientation to the person's

friends or family against the person's wishes; threatening to withhold a person's medication; preventing a person from making or keeping connections with the person's

family, friends or culture, including cultural or spiritual ceremonies or practices, or preventing the person from

expressing the person's cultural identity; threatening to commit suicide or self-harm with the intention of

tormenting or intimidating a family member, or threatening the death or injury of another person.

Unfortunately, additional powers have been granted to the police whereby

they can issue „safety notices‟ ordering a person out of their home even though their

name is on the title, purely with the approval of their sergeant. The respondent can be

detained for 6 hours and a further 10 on application by fax or phone. The Officer can order the

respondent to not return to their home. The order remains in force until a court hearing can be

arranged, supposedly within 72 hours, plus allowances for public holidays. The first mention

does not provide an opportunity for the respondent to present any evidence or arguments

against the imposition of an ouster order. Certainly seems to be a case where the punishment

imposed by an ouster order symbolises a penalty for a guilty person, regardless of

their innocence or not. If we are prepared to toss away any notion of innocent until proven guilty

we may as well abandon the prospect of retaining a fair judicial process.

A respondent will not be allowed to cross examine the complainant – too

bad if they cannot afford a lawyer, (Legal Aid almost never supports a defendant to a

domestic violence application); a child over 14 can apply for an order against his/her

parents; the Act allows for others close to the accused to become co-accused; one no longer needs to

„consent‟ to an order just don‟t actively oppose one for an order to be issued; just

having children in the house when an argument between the parents occurs can result in a

domestic violence order to protect the children.

Despite Family Court orders providing contact, under this domestic

violence Act orders can be suspended. Imagine spending anywhere between $10,000 and $140,000 to

gain orders to see one‟s children, only to find it prevented when the other parent

claims new Page | 31

circumstances have arisen and applies for a domestic violence order or a

renewal of an expired order.

The following section 176 contained in the FVPA 2008 refers to the

abovementioned situation: 176 Relationship with Family Court orders A family violence intervention order operates subject to any declaration

made under section 68Q of the Family Law Act by a court having jurisdiction under Part VII of that

Act. Note Section 68Q of the Family Law Act provides that a court exercising

jurisdiction under that Act may make a declaration that an order or injunction under that Act is inconsistent with a family

violence intervention order. To the extent of the inconsistency, the family violence intervention order is invalid. See

also section 68R of the Family Law Act which provides that a court exercising jurisdiction under this Act may revive,

vary, discharge or suspend certain Family Law Act orders.

NSW, Tasmania and Western Australia also allow police and courts to

issue orders restraining a person accused of domestic violence without given them the

opportunity of a court hearing, raising the „suggesting that making an order before a

person had been tried “may readily be seen as a denial of justice”‟

32

. In Tasmania many complaints have been heard, even from the legal profession about the ability granted under

their Act to profile the accused and imprison them until a court hearing can be arranged.

Unfortunately, the AGS review of domestic violence laws does not

consider the new Victorian legislation, (p.69).

Much more can be said on the misuse of domestic violence laws and the

State governments‟ encroachment on civil liberties without reasonable cause.

A recent letter sent to the Attorney General explains the conflict

caused between domestic violence programs clearly providing services for women only and the

requirements of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as

follows:

The proposed spending of $38.5 million, as enunciated in the media

release of 29 April, is essentially designed to make a protection (ie. freedom from violence)

through government policy and service delivery dependent on the victim‟s gender. In my opinion,

this is a crude violation of one of the most fundamental and cherished principles of international

human rights law. Articles 2,

32

AGS,2009 Domestic violence laws in Australia, p.31) Page | 32

4 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

(ICCPR), to which Australia became a party in 1980, and which in turn reflect the rights set out in

Articles 2, 7, and 16 (1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, are quite explicit and

uncompromising in this matter and prohibit discrimination based on sex. Article 26 of the ICCPR, in

particular, guarantees “to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any

ground such as, inter alia, sex”.

Further, the policy also explicitly violates Article 23 (4) of the ICCPR

requiring Australia to “take appropriate steps to ensure equality of rights and responsibilities of

spouses … during marriage and at its dissolution”. The shared parenting laws, besides conferring

the right of children to the benefit of a meaningful relationship with both parents, also go some way

towards implementing equal rights at the dissolution of marriage since property and parenting

are essentially the only areas where this provision could have any possible application.

In the context of a domestic violence policy that makes protection -

through advocacy and service delivery – contingent on the victim‟s gender, this would mean that a

woman suffering domestic violence or spousal abuse during marriage would have access to an

extensive range of government service delivery to afford her protection, but a husband who

suffered the same violence or abuse in marriage would be precluded due solely to his

gender. This clearly violates Article 23 (4) of the ICCPR as it produces complete inequality and power

imbalance during marriage given that domestic violence is probably the most egregious and

abhorrent crime that a person can possibly suffer as a result of entering into marriage.

One could even argue that the government‟s policy on domestic violence

amounts to incitement to discrimination in violation of Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights. Roger Smith, Canberra

Suffice it to say this Agency is extremely concerned that the new

Victorian legislation has deemed it appropriate to refer to men as being the majority perpetrators

of domestic violence, which will encourage some to regard the FVPAct 2008 as purely

for the use of women. What response will a man, who has been deemed to be in the

minority as a victim, receive from a court operating under legislation giving clear

indications to accept women are in the majority, when it comes to being a victim of domestic violence?

Does this mean, when in doubt about the truth of competing claims made by both parties, a

magistrate may be tempted to defer to the doctrine prescribed in the preamble and find on

the balance of probabilities that the woman is more likely than the man to be the

victim? Page | 33

The Women‟s Legal Service Victoria has already claimed ownership of the

Act by using a masculine adjective on three separate occasions in the document they

prepared entitled - Comparison Table Navigating the new Family Violence Protection Act

200833

. See below:

Conditions (s80 and s81) Court may include ANY CONDITIONS that appear necessary or desirable

in the circumstances ‐ s81 �� Allow the respondent to collect his things in presence of police or other specified person

Conditions ‐ Personal property (s86‐88) The court MAY include conditions relating to the use of personal property including – s81(2)(c) and s86 …. o Allow the respondent to collect his personal property in presence of police or other specified person – s86

Rehearings (s122) If the respondent was not personally served with the application AND

it was not brought to his attention under an order for substituted service the respondent may apply for a rehearing at the Magistrates’

Court. An application for a rehearing does not stay the operation of

the order.

False Allegations:

117AB Costs where false allegation or statement made (1) This section applies if: (a) proceedings under this Act are brought before a court; and (b) the court is satisfied that a party to the proceedings knowingly

made a false allegation or statement in the proceedings. (2) The court must order that party to pay some or all of the costs of

another party, or other parties, to the proceedings.

33

Comparison Table Navigating the new Family Violence Protection Act 2008

http://www.justice.vic.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/DOJ+Internet/resources/file/ebd51940033357b/FamilyViolenceAct_comparisson_table.pdf

Page | 34

Section 117AB provides for a cost order to be made against a party found

to have knowingly made a false allegation or statement. Women‟s groups are

lobbying intensely to have this section removed.

A search of cases listed on austlii.edu.au under „false allegations‟

provides access to six decisions given as a result of an appeal heard in the Full Court of the

Family Court of Australia. Despite there being some mention of „false allegations‟

having been made, none resulted in a costs order issued under 117AB.

In one case where costs were claimed under s117AB- Carpenter and Lunn

[2208] FacCAFC 128, both parties were awarded a costs order pursuant to the

Federal Proceedings (Costs) Act 1981

A further search for „false allegations‟ in the Family Court of

Australia produced 109 cases. Of those, 91 cases were dated later than July 2006. Only 13 of those

cases responded to the search query s117AB.

The first case listed does provide some small portion of relief under

s117AB for the husband based on the finding the wife did make false allegations. He was awarded

only 25% of his trial costs. His overall costs had reached at least $43,000. The wife

was ordered to pay $3,195 with 9 months to pay. Sharma & Sharma (No. 2) [2007] FamCA 425 (2 March 2007)

24. The wife emphasises that the husband initiated these proceedings.

She says the proceedings were unnecessary and the issues which concerned the husband were capable of exploration and

resolution more cheaply in the domestic violence proceedings. This submission side steps that the apprehended violence

proceedings sought, at order 13, to prohibit contact between the husband and the children. I accept the husband‟s

submission that in order to preserve his relationship with the children, he required this Court‟s intervention and

consideration in a wider sense, of the impact upon him and the children of the wife‟s actions. Mr Jurd pointed out that following

upon completion of the 2004 parenting proceedings, it is apparent the husband kept a detailed diary concerning

matters involving the wife and his contact with the children. To a considerable degree, this demonstrates the husband

prepared for another round of litigation. I accept he did. It seems likely however, that he prepared to defend further

allegations from the wife rather than initiate proceedings against her. The wife forced his hand when she took her

complaints and allegations to police and others. This finding weighs in favour of the husband‟s costs application. 25. The next issue requiring consideration is whether the husband‟s

costs ought to be ordered on an indemnity basis. In Kohan & Kohan (1993) FLC 92-340 the Full Court held that an indemnity

costs orders is a very great departure from the normal standard. Their Honours cited with approval Sheppard J in Colgate

Palmolive Co & Anor v Coussins Pty Ltd (1993) 46 FCR 225. Sheppard J lists examples of circumstances which have resulted

in indemnity cost awards. Relevantly, these include: “Making of allegations of fraud knowing them to be false” and

“the making of allegations which ought never to have been made”. Concerning indemnity costs, His Honour held: Page | 35

“The question must always be whether the particular facts and

circumstances of the case in question warrant the making of an order for

payment of costs other than on a party and party basis”. 26. In the family law context, however, as the Full Court said in Kohan:

“Even in cases where there has been dishonest concealment of assets or

income .... No more than party and party costs have been awarded”. 27. Arguing against indemnity costs, Mr Jurd highlighted that the

commencement of the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibility) Act 2006 changed the applicable law and that it

was reasonable, having regard to Dr Q‟s report, for the wife to resist the husband‟s primary and alternate applications.

Particularly when one considers the children‟s desire to continue living with their mother and that she has been their primary

carer all their lives. I do not accept Mr Austin‟s submission that at least from release of Dr Q‟s report the wife‟s

position was untenable. Although Dr Q‟s report and evidence seriously damaged the wife‟s allegations, neither party, nor

their legal advisers, could have confidently predicted the outcome of these proceedings. 28. Thus, notwithstanding that other courts have determined that “the

making of allegations which ought never have been made” warrant an indemnity costs order, having regard to the totality of

circumstances in this case, I am not persuaded an indemnity costs order is appropriate. 29. Calculated in accordance with the Family Law Rules, since 14

December 2004 the husband incurred costs in the vicinity of $43,000. Concerning the hearing, other than 25 September

2006, counsel appeared uninstructed. The trial costs are $12,780. Concerning affidavit preparation, I have no